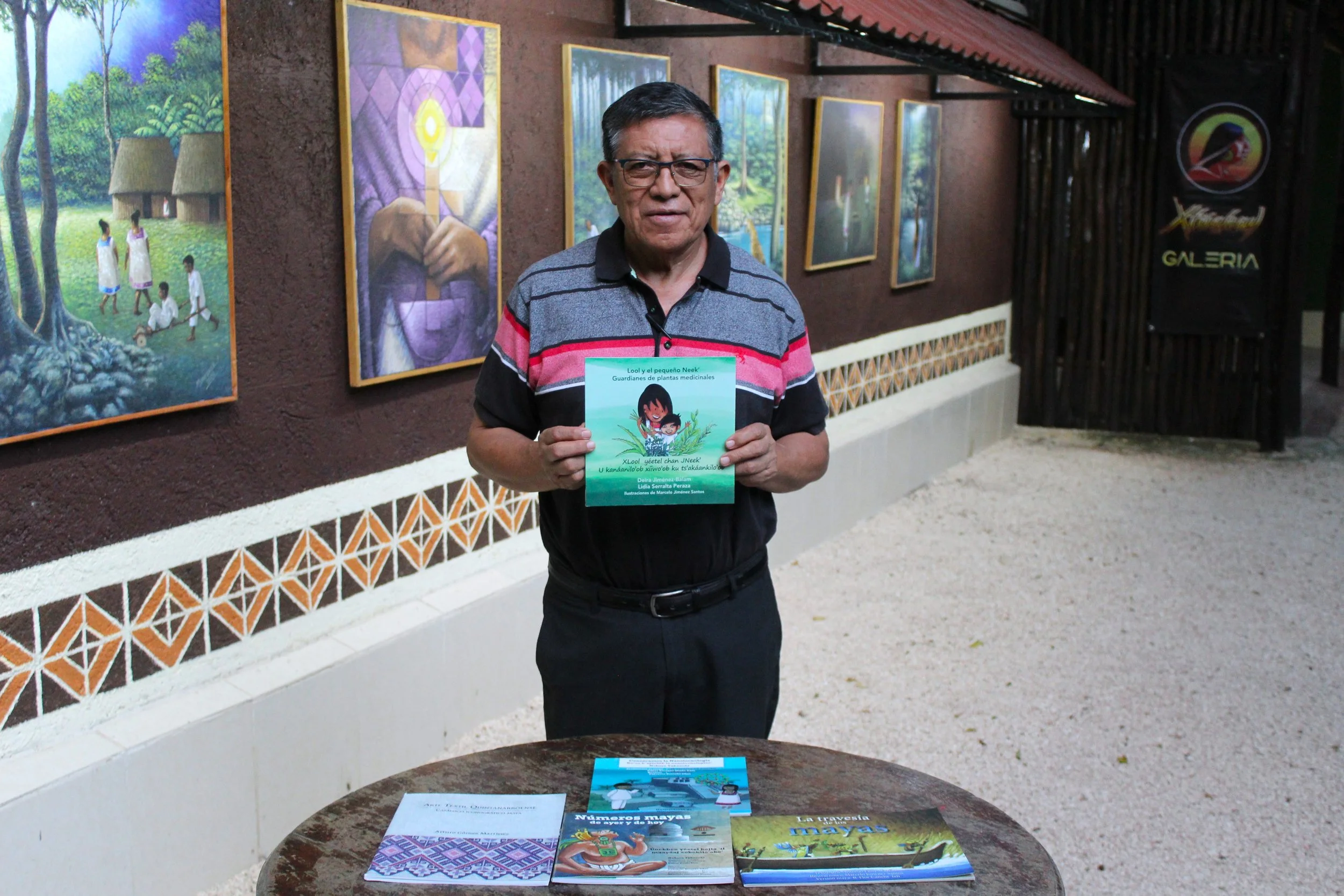

Faces of Na'atik: Marcelo Jiménez Santos

Marcelo Jiménez Santos, a painter originally from a town called Noh Cah, has a very interesting family history. He not only portrays his experiences and history in his paintings, but he is also part of what he seeks to reflect and communicate about his culture, about the knowledge he acquired from his community and that he hopes will continue to be preserved for many future generations.

We are in a city that was an important historical center during the time of resistance and the Caste War. How do you address in your paintings a topic that may be sensitive for some people?

I have approached it from an artistic and historical perspective, and also because I belong to this territory and have relatives with a very interesting history. I do not have a Maya surname, because my parents’ first surnames are in Spanish, although their second surnames are in Maya, and I did not inherit those.

I am Jiménez Santos, but I used to ask myself: where do the Jiménez come from to be in this territory of resistance, of more than half a century of autonomy? I asked my father, may he rest in peace: “Where do we Jiménez come from? How is it that we are in this rebellious territory, in resistance?”. He told me that during the time of the war, when they were moving from Valladolid to Tihosuco, his ancestors were ambushed. The adults were executed and the children were taken to a place called Pom, near Laguna Canal, where they settled.

One of my uncles is a founder of Laguna Canal, where they opposed the opening of schools in that area, since at that time the government was not allowed to enter at all. It was an autonomous territory that resisted the government system.

Was there ever a moment when you felt you did not fully belong because your surnames are not Maya? Or that this part of your history with your ancestors affected your sense of identity?

I was born and raised in a Maya-speaking family. For example, my mother, may she rest in peace, did not speak Spanish. She is the great-great-granddaughter of the Maya General; she is Santos Maya.

We always spoke Maya. When I’m at home, I speak Maya with my siblings. I had never identified a particular origin or identity until I grew older. I arrived here in 1976, and it was only when I began to get involved in cultural promotion that I realized I have a very interesting historical origin, that I was part of those who fought starting in 1847 with the beginning of the Maya Social War and the founding of the city in 1850, and everything that followed until 1901, when this city was occupied by the federal army.

Additionally, around 1920, the Maya General was the highest leader of these rebel groups until 1928, when the peace agreement with the Mexican government was signed and we accepted being Mexican. The Maya General was no longer recognized as leader and emigrated, later returning to the town where I am originally from. I remember seeing him when I was a child, because he would come to talk with my father, and they would tell me, “Go to sleep, go to sleep,” because those were conversations among elders.

These are parts of very interesting stories that made me more aware, and thus I began to get more involved in that topic and also in the issue of living Maya people, their cultural expressions, and the ancestral exclusion of not being recognized. As Indigenous communities, we also have contributions to offer the world, we have science, mathematics, astronomy, we have everything. We are simply different.

When I speak of culture, I’m referring to ways of life: how we live, what we eat, how we organize ourselves, how we dress, how we sleep, what we dream. All of that is part of our culture, and we acquire it through the context in which we interact. No one is without culture. People often say, “What culture could there be in that town?” Maybe Western culture is not present, but local culture is, and everyone is cultured, just in a different way.

How do you reflect in your art or daily life the evolution of contemporary Maya culture, compared to what someone with little contact might imagine?

The culture shock is significant because our education system is Eurocentric. Everything we are taught and consume educationally comes from outside, and we don’t contribute from here outward; instead, everything comes to us.

It is complex, because the more we are educated, the more we distance ourselves from our origins, in this case Maya, because we are told about the Greeks and others, but local history is rarely addressed.

Not everyone accepts that Indigenous people have made contributions. However, some people have become more aware, reeducated themselves, and mentally decolonized, leading to recognition of local culture. Every place has its own ways. Each person knows where they come from and is an expert in their place of origin. Someone from an urban area understands urban life; someone from a rural community knows how to move through the forest, which fruits to eat, and so on.

Today, the new generations of Mayans are part of global dynamics. They participate in all areas. Sometimes people ask, “Where are the Mayans now?” Those who didn’t pursue formal studies still have training; instead of building pyramids, they are building hotels, they are still here. Those who entered academia are also contributing, but from here outward, from the local to the Western world.

Now the Mayans are global Mayans. Fortunately, we have an intercultural university that recognizes local contributions. Students have elder mentors; beyond classroom instruction, they must also learn from community elders, because communities have their own pedagogy, transmitting knowledge differently from Western classrooms.

How did the gallery project begin?

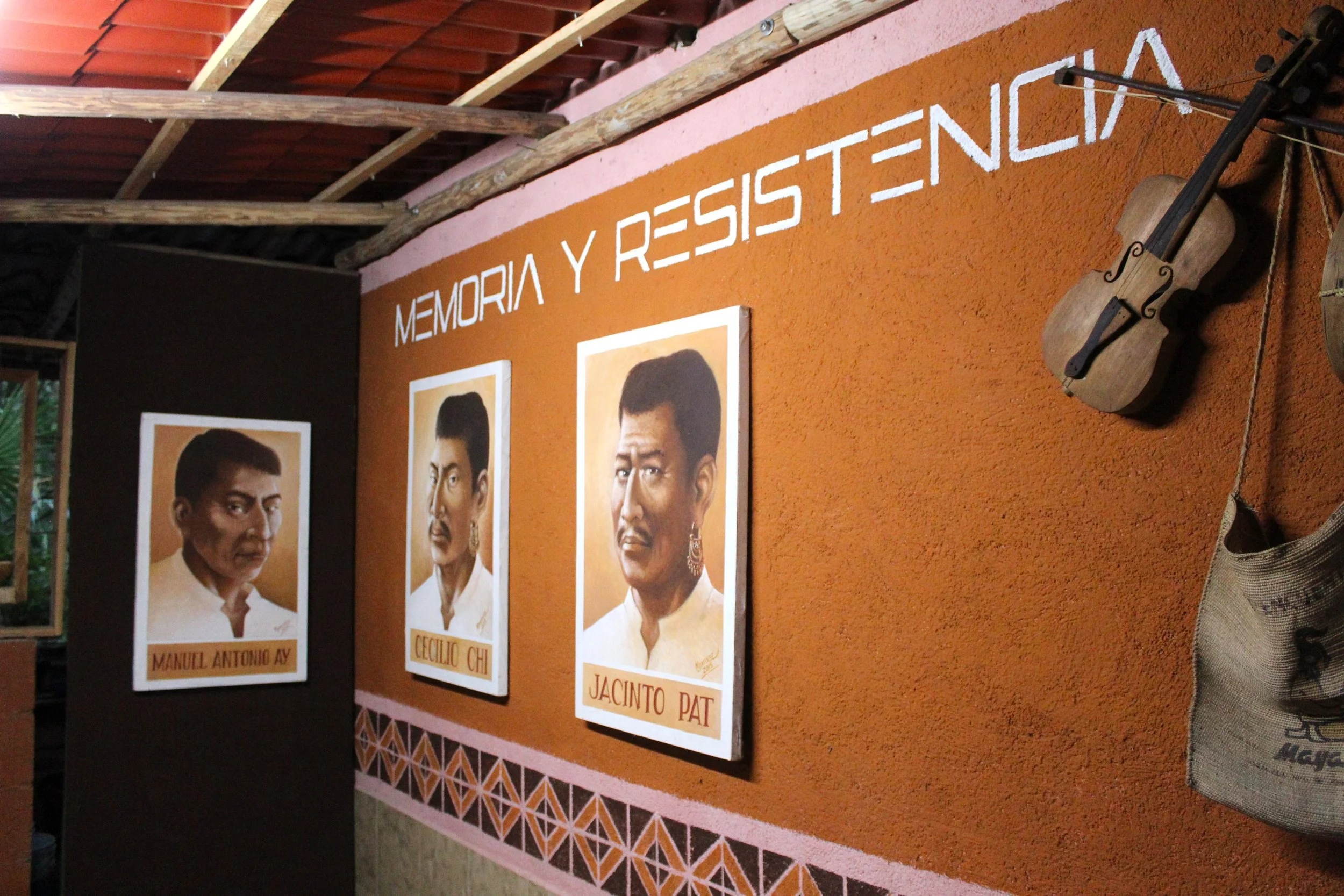

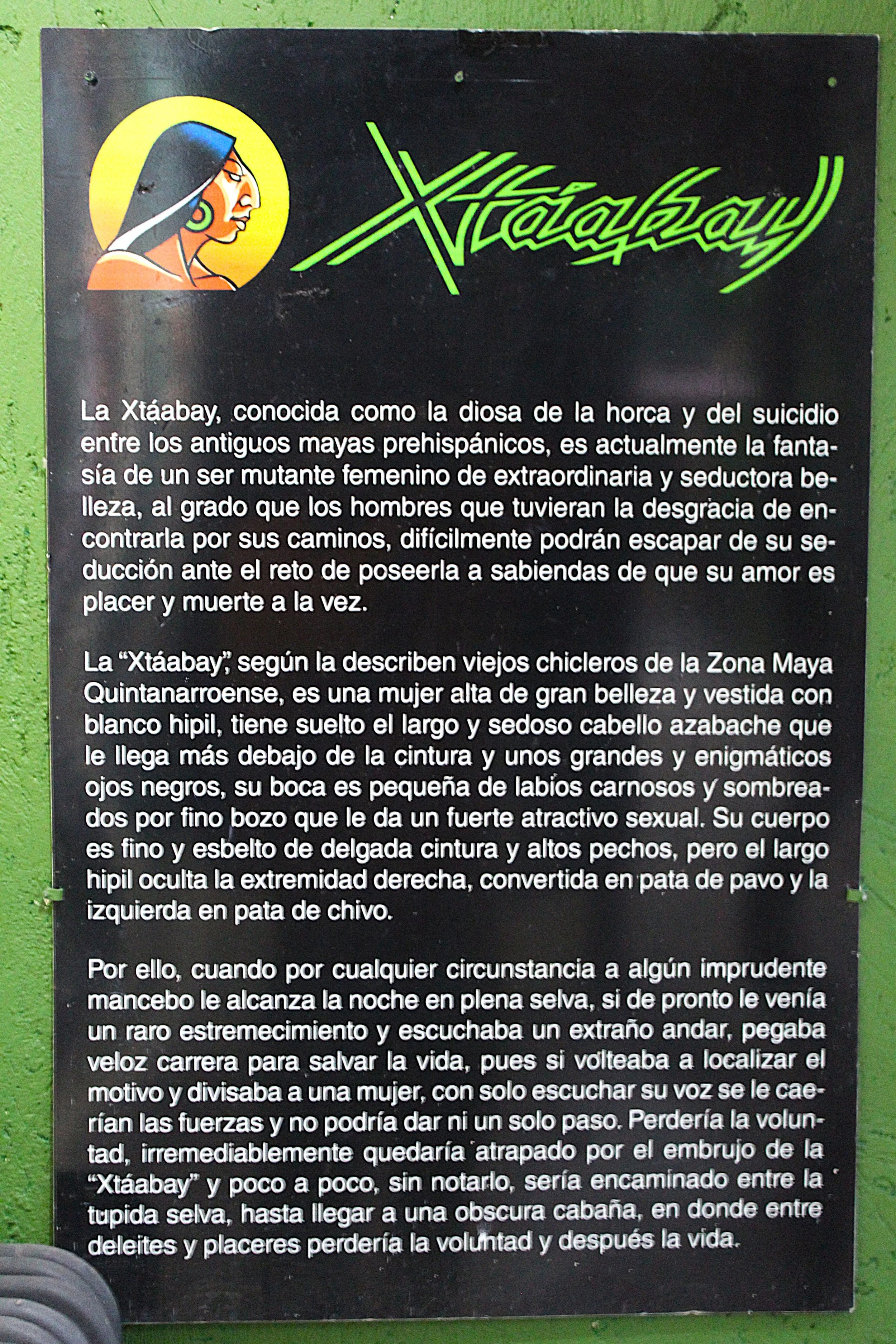

The gallery is called Xtáabay, and I’m envisioning it as a cultural center, because there will not only be exhibitions but also other activities. Currently, on Fridays there is music, and we plan to develop diverse activities. It is a family and personal project, with no institutional program involved. Everything built has been self-funded.

The goal is to create an alternative space for emerging expressions that do not always find room in institutional venues. Here, people can present music, literature, gastronomy, and perhaps traditional food showcases in the future. We want it to be a diverse space for different groups with specific interests and to recreate spaces for living cultural expressions without altering their context, we want to offer authentic experiences.

I plan to put up a sign that reads: “Art, memory, and cultural resistance.” For me, simply speaking Maya is an act of cultural resistance. Maya is a vehicle for transmitting intangible heritage, because everything I learned about the countryside, the milpa, melipona bees, gum, and more, was learned in Maya.

If you had to suggest one thing someone needs to open their mind to new cultures and ways of thinking, what would it be?

I would invite them to spend time in the territory itself, beyond academia. Today, people have the world on a computer, but without going into the territory, theory is of limited use. People should not stay confined to a screen but interact directly. I see foreign researchers who come to live in communities. I know French and German people who build Maya-style houses and live in them for six months at a time. After five years of this, they speak Maya, live with Maya families, and eat with them.

We also tend to value what comes from outside more than what is our own. Since colonization, we were told that nothing from here was worthwhile, and we believed it. So we discarded our own heritage. But gradually, new generations are recognizing its value; cultural expressions like gastronomy and embroidery are gaining recognition.

Many people say, “I don’t speak Maya,” but sometimes you can tell, for example, in places like Tulum or Playa del Carmen by their accent. Something similar happens with Latino migrants in the United States who say, “I don’t speak Spanish.”

Sometimes people feel the need to adopt identity elements to be accepted in another group. Identity is not lost; rather, new elements are acquired to integrate elsewhere. When you return home, you don't speak another language, you speak your native language. You deactivate one identity element and activate another depending on context. The more languages we speak, the more opportunities we have to interact with the world.

To learn more about Na’atik’s English language program for local and Indigenous students in Felipe Carrillo Puerto, visit our Impact Page. We are only able to provide this much needed program thanks to the support of generous donors and the funds raised from our award winning Maya and Spanish Immersion Program. If you would like to support our mission please consider donating today or take a look at our immersion programs and online class packages.